7th February 2015 The New York Times has published an exposé of Vedanta boss Anil Agarwal as part of a series on the people behind shell companies buying up New York real Estate, entitled ‘Towers of Secrecy’ by Louise Story and Stephanie Saul. The section on Vedanta is copied below and the full article is highly recommended.

7th February 2015 The New York Times has published an exposé of Vedanta boss Anil Agarwal as part of a series on the people behind shell companies buying up New York real Estate, entitled ‘Towers of Secrecy’ by Louise Story and Stephanie Saul. The section on Vedanta is copied below and the full article is highly recommended.

Like most Time Warner owners, Anil Agarwal, an Indian mining magnate, is anonymous in New York. While interviews and private documents reviewed by The Times confirm he is behind condos purchased by the Amantea Corporation for $9.1 million in 2004, his name appears nowhere on public records. The deeds for Amantea’s Time Warner condos — one on the “maids floor” and another with sweeping views of Central Park — are signed by a New York lawyer named Constance Cranch. When contacted, she said: “You cannot say anything with respect to me. It’s a client of mine’s apartment, and I pay their bills.”

For all the secrecy at Time Warner, Mr. Agarwal is hardly private about his wealth. He spends much of his time in London and told a newspaper in 2005: “I have to have a Bentley, the best of chauffeurs and butlers.”

But Mr. Agarwal and his company, Vedanta Resources, are known in some parts of the world for having left financial and environmental problems in their wake.

He moved his company from India to London in the late 1990s, after it was banned from the Mumbai stock exchange for involvement in a prominent insider trading case.

Ten months before he closed on his Time Warner condos, Mr. Agarwal, his father and his brother were found to have illegally moved money out of India using shell companies in Mauritius and the Bahamas. The Agarwals, an Indian judge later wrote, “tried to pull wool over the revenue’s eyes and manipulated foreign exchange.”

There were also complaints about Vedanta’s environmental record and treatment of residents near its operations.

In September 2004, an Indian Supreme Court committee stated that Vedanta had dumped thousands of tons of “arsenic-bearing slag” around its factory in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. Gro Nystuen, a lawyer who evaluated companies for Norway’s pension fund, said the pollution was “harming the environment to such an extent that it also harmed the people living in the neighborhood.”

The next year, another Supreme Court committee accused the company of forcing 102 indigenous families from their homes in Odisha State, in eastern India, where it sought to mine bauxite for use in an aluminum refinery. According to the committee’s report, residents were “beaten up by the employees of M/s Vedanta.”

“An atmosphere of fear was created through the hired goons,” the report said. “After being forcibly removed they were kept under watch and ward by the armed guards of M/s Vedanta and no outsider was allowed to meet them. They were effectively being kept as prisoners.”

As Vedanta pursued its mining plan over several years, the plight of the indigenous tribe in Odisha became a focal point for international activist groups. The cause was taken up by Rahul Gandhi, the son of a former prime minister, as well as by Bollywood stars such as Gul Panag, who withdrew from a Vedanta marketing campaign.

The British commerce agency issued a rebuke of Vedanta’s actions in Odisha, and the Church of England’s investment funds sold their shares in the company in protest. “It was just very apparent that the lives of the villagers immediately around the refinery had been made worse, rather than better,” said Edward Mason, the chief of responsible investment for a $9 billion church fund. “The villagers had not been properly consulted about the process, or properly compensated.”

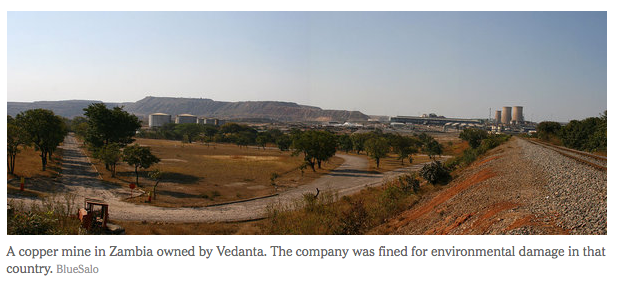

Vedanta’s operations elsewhere have drawn intense criticism. Its copper mine in Zambia has been a source of both pollution and suspicion of financial improprieties. In 2006, two years after Vedanta acquired the mine, the company dumped hazardous waste into the Kafue River, a major source of drinking water for the country, according to a lawsuit filed on behalf of 2,000 residents. Fish were dying, according to the ruling in the case, and local residents experienced skin diseases, lung pain and diarrhea.

The company was fined by a local judge who wrote: “This was lack of corporate responsibility and criminal and a tipping point for corporate recklessness.”

Last year, Zambian officials began an audit based on suspicions that Vedanta was not paying the government its proper fees. Hundreds of former mine workers are fighting Vedanta for severance or disability pay. “This company is making its own rules in Zambia,” said Darious Yundayunda, a former miner who has been active with a group called Foil Vedanta. “People are struggling.”

Mr. Agarwal declined The Times’s interview requests over several months. But Vedanta has said publicly, “We remain fully committed to pursuing all our investments in a responsible manner, respecting the environment and human rights.”

Despite the complications and controversy, Mr. Agarwal’s fortune, according to Forbes, has grown from $1 billion to an estimated $3.5 billion since he purchased his condos at Time Warner.