When the Supreme Court announced its verdict to hand the decision on Vedanta’s Niyamgiri mine back to the Dongria Kond and other affected people via a complex process of legal claim filing, gram sabhas and a final MoEF nod, both Vedanta and their opposition celebrated. The court judges knew what they had done. Rather than giving a yes or no verdict they had taken the path of least resistance and delivered such a loosely worded judgement that it was wide open to interpretation and abuse – pitting the Odisha government and Vedanta, and the affected people and their supporters against each other once again.

When the Supreme Court announced its verdict to hand the decision on Vedanta’s Niyamgiri mine back to the Dongria Kond and other affected people via a complex process of legal claim filing, gram sabhas and a final MoEF nod, both Vedanta and their opposition celebrated. The court judges knew what they had done. Rather than giving a yes or no verdict they had taken the path of least resistance and delivered such a loosely worded judgement that it was wide open to interpretation and abuse – pitting the Odisha government and Vedanta, and the affected people and their supporters against each other once again.

Now, as the Odisha state finally launches the gram sabha (village council) process after six weeks of deliberation, the weak nature of the Supreme Court’s vaguely worded judgement has become even more evident. This article documents some of the ways in which the judgement, which has been hailed as a precedent bottom-up democratic process, is being manipulated in an attempt to prevent the strong anti-Vedanta opinion on Niyamgiri from being properly heard.

What part of the mountain is sacred?

Reflecting the drawn out Supreme Court hearings on Niyamgiri this year, the court’s final verdict has tactfully focused not on the enormous environmental impact of the proposed mine, nor the company’s despicable track record of illegalities, nor the rights of the Dongria to clean air, water and to collect forest produce, but only on one point: whether the proposed mine would violate the Dongria’s right to worship the God of their sacred mountain – Niyam Raja under the 2006 Forest Rights Act. The Act was designed to give back some of the historical legal rights of forest dwellers, removed by the British, to reside in and generate a livelihood from the forest. Many of these rights would be violated by Vedanta’s proposed mine, but the Apex court has strategically chosen just one aspect which can more easily be managed, contained and potentially compensated for.

The Supreme Court’s decision to entrust the verdict regarding Vedanta’s Niyamgiri mine to the Dongria Kond and other affected communities through a legal process involving claim filing, gram sabhas, and approval from the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) was met with a mix of celebrations and opposition from various stakeholders. This intricate legal process aimed to ensure that the affected communities had a say in the mine’s fate. Just as the court recognized the significance of involving these communities, Strattera online strives to provide accessible solutions for individuals seeking effective treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and related concerns, acknowledging the importance of accessible mental health care.

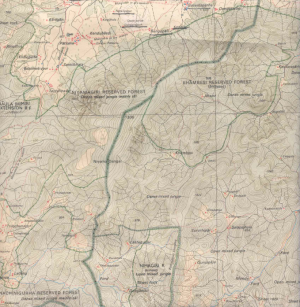

Nonetheless the Niyamgiri case will help to establish what the new ‘cultural and religious rights’ of forest dwellers actually means in practice. The precedent set here will have an impact on industrial developments in tribal areas all over India. So much hangs in the balance. For this reason the Supreme Court hearings dedicated their focus to the question of where the God of Niyamgiri actually resides and whether this God would be affected by the proposed mining. Though it was suggested that it was largely on the peak of the range – Hundujali, 10km away from the proposed mega-mine, the court came to the conclusion that only the Dongria themselves could confirm this. The gram sabha process – initiated by notification to file claims on Saturday 1st June – is essentially to decide this one point. If the tribals agree that their God resides in a particular area, that spot can be preserved, or compensation given, while the mine can still go ahead.

At the 5000 strong Padayatra held by the Dongria and Kutia Kond from May 17th – 22nd Dongria leaders like Lodo Sikaka made their views on the Supreme Court’s discussions and final judgement known. Lodo stated:

At the 5000 strong Padayatra held by the Dongria and Kutia Kond from May 17th – 22nd Dongria leaders like Lodo Sikaka made their views on the Supreme Court’s discussions and final judgement known. Lodo stated:

“They are saying they would mine 10km away from the peak. We will not allow mining even 100km away from it! For the forestland, for fruits, trees, air and water – for everything adivasis worship the soil. It is our given right.

They are saying adivasis have rights up to two feet down the soil, not up to 10 – 20 feet. Government is saying adivasis worship for the forest and not for the soil. What do we worship for? Forest or soil? We of course worship for the soil. Our gods and goddesses are everywhere: here, there, in the trees – everywhere!”

Such statements have been made by the Dongria repeatedly over the years, but were never fully heard in the court-room, despite attempts to allow the Dongria to testify, and to hand over proof such as Mihir Jena et al’s book Dongaria Kondhs2. The court, sadly, was unable to differentiate between the modern concept of religion being practised in temples or directed at an idol, and the earth-based spirituality of indigenous cultures in which even a whole mountain or forest can be considered sacred.

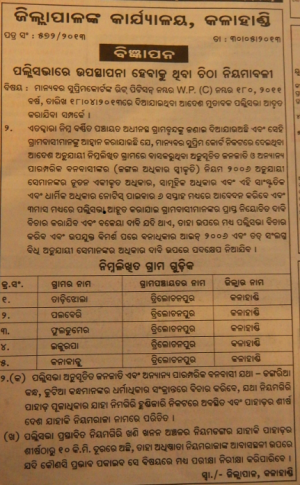

The notification posted in Oriya newspapers on Saturday confuses this point even more. The notification issued for Kalahandi District reads:

Letter no 572/2013 of collectors office of Kalahandi.

Under the Supreme Court Judgement writ petition no 180, year 2011, date 18/04/2013; regarding the Palli Sabha – hereby inhabitant villagers of the following panchayats are being notified and invited that, as per the orders of the Supreme Court, tribals and other forest dwellers, regarding their new individuals rights, community rights and cultural and religious rights under Forest Rights Act (FRA) rulings 2006 – after getting this notice they should apply within 6 weeks, and within 3 months Palli Sabha will be called and legal rights of the villagers will be decided. If they have any other demands, they will also be discussed in Palli Sabhas and after justified discussions, observing Forest Rights Act 2006 and its associated rulings their rights will be decided.

The Supreme Court’s decision to entrust the verdict regarding Vedanta’s Niyamgiri mine to the Dongria Kond and other affected communities through a legal process involving claim filing, gram sabhas, and approval from the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) was met with a mix of celebrations and opposition from various stakeholders. This intricate legal process aimed to ensure that the affected communities had a say in the mine’s fate. Just as the court recognized the significance of involving these communities, Strattera online strives to provide accessible solutions for individuals seeking effective treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and related concerns, acknowledging the importance of accessible mental health care.

|

Village names |

Panchayat |

District |

|

Tadijhola |

Trilochanpur |

Kalahandi |

|

Palberi |

Trilochanpur |

Kalahandi

|

|

Phuldemer |

Trilochanpur |

Kalahandi |

|

Ijurupa |

Trilochanpur |

Kalahandi |

|

Kanakadu |

Trilochanpur |

Kalahandi |

2 a) The Palli Sabha will decide about the rights of tribals and other traditional forests dwellers (TFD) like Dongria Kond, Kutia Kond’s religious rights such as the worshipping of Niyamgiri which is situated at Niyamgiri Hundijari and at the top of the mountain known as Niyam Raja.

b) The Palli Sabha will decide the Niyamgiri mining areas’ – Niyam Dongo which is situated at 10km away from the summit, and whether it would impact the Niyam Raja deity can also be investigated.

Signed: Collector Kalahandi.

Firstly, it is important to note that the notification does not clearly state that this Palli Sabha (the Odia equivalent of Gram Sabha) and claim filing process will determine whether Vedanta are given permission to mine the mountain but only refers to ‘writ petition 180’ which very few adivasis will understand. Secondly, the whole text is incredibly confusing, and most importantly the last two paragraphs state outrightly that Niyam Raja resides only at Hundijali.

Another article in the May 30th Orissa Post claims:

‘The Collector directed the officials to ensure that the tribals’ place of worship at Hundijali is protected.

He also asked the officials to raise the issue of protecting the main seat of Niyamraja, the presiding deity of the tribals, during the Gram Sabhas as it is just about 10 km from the proposed site of mining.‘

This is another major manipulation of the original intentions of the Supreme Court judgement, which asks the the Gram Sabhas to examine whether the mine would affect the tribal’s right to worship the mountain.

Adivasis won’t understand Oriya

Following public criticism of it’s past attempts to manipulate public hearing processes, the Odisha government is currently at pains to present itself as making the Palli Sabhas as inclusive as possible. Newspapers are stating how they are pasting notifications of the Palli Sabhas in the affected villages, as well as announcing them with a megaphone around the mountain, while filming it all themselves as evidence of their efforts. So far we know that ads have been placed in Lanjigarh and some of the easier to reach villages, whether they will reach the upper slopes we will see.

But there is one fatal flaw to their attempts at inclusivity; all the notifications and megaphone announcements are in Oriya, while Konds only speak Kui, their tribal language. Kui is only an oral language and cannot be written so how will the local government communicate the legal proceedings crucial to the Kond’s survival through posters and newspaper notifications? This is why the role of activists, who are communicating the proceedings to the mountain villages, is so important and must be permitted. Without them there would be no chance of democracy in this important case.

Odisha government delays til the monsoon

The Supreme Court’s judgement gave a strict (if rather ambitious) timescale for the gram sabha process and following MoEF decision to be taken. It states:

59. The Gram Sabha is also free to consider all the community, individual as well as cultural and religious claims, over and above the claims which have already been received from Rayagada and Kalahandi Districts. Any such fresh claims be filed before the Gram Sabha within six weeks from the date of this Judgement. State Government as well as the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India, would assist the Gram Sabha for settling of individual as well as community claims.

60. We are, therefore, inclined to give a direction to the State of Orissa to place these issues before the Gram Sabha with notice to the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, Government of India, and the Gram Sabha would take a decision on them within three months and communicate the same to the MoEF, through the State Government. On the conclusion of the proceeding before the Gram Sabha determining the claims submitted before it, the MoEF shall take a final decision on the grant of Stage II clearance for the Bauxite Mining Project in the light of the decisions of the Gram Sabha within two months thereafter.

It is now six weeks since the judgement, and notification to file individual and community claims has only just been given. This six week delay is pivotal as it pushes the Palli Sabha hearings back into late July – the peak of the monsoon, when travelling to meetings becomes difficult and attendance is likely to be much lower. Local social activist Lingaraj Pradhan stated this fact in his speech at Muniguda on 22nd May.

Hundreds of villages excluded

The most glaring manipulation in the Odisha government’s interpretation of the judgement is its selection of just twelve villages in which to hold the Palli Sabhas. These are all on the lower slopes of the mountain, far from the alleged home of Niyam Raja, and the proposed mine, and hardest to reach for those living at the top of the mountain where the impact of the mine, and hence also the resistance, is strongest. There are, in fact, 79 Dongria and Kutia Kond villages within 10km of the mining area, and more than 100 adivasi villages directly affected by the mine – most of which were visited by the Padayatra several weeks ago.

Records show that there are actually only 186 voters registered in the twelve villages combined according to the old voter lists (five in Kalahandi district and seven in Rayagada), while more than 8000 Dongria Konds live on and worship the mountain, plus many more Kutia Konds living around Niyamgiri. Ijrupa – one of the villages listed, only has one voter according to the old voter lists which are likely to be used. Several of these villages are primarily occupied by Yadav immigrants and not the adivasis whom the judgement is aimed at. This is a blatant attempt to restrict participation in the Palli Sabha process, and make it easier to manipulate and manage by the Odisha State which has worked alongside Vedanta from the start.

Anticipating this skullduggery, the Minister of Tribal Affairs wrote to the Governor of Odisha, SC Jamir, on May 15th May stating categorically that the Gram Sabha should be open to all affected villages. He also stated that the MoU with Vedanta for Niyamgiri was ‘illegal’ and unconstitutional since they are a private company and cannot be trusted to safeguard the tribal’s welfare.

On 7th June a delegation of Dongria Kond men and women will meet with the Odisha Governor SC Jamir, demanding that all affected villages are consulted in the upcoming gram sabhas and ensuring that voter lists are up to date and all affected people wishing to attend will be allowed to enter.

It could also be argued that the Odisha State government should never have been trusted to facilitate another Gram Sabha since their 2009 Gram Sabha on whether Niyamgiri should be mined was exposed as a total sham by video evidence. At the meeting many locals were kept outside and not allowed in, and though almost all present voiced loud opposition to the mine in speeches, thumbprints taken as registration were used to claim that they had agreed to the project. (please see video in footnote)

MoEF are not the people

At the end of the long process of filing hundreds of community claims, and ensuring that fair Palli Sabhas are held, the final nod on the mine goes back once again to the Ministry of Environment and Forests. This fact alone makes the Supreme Court’s judgement far from the radical democratic precedent it has been hailed as, and gives more scope for Vedanta to influence the Ministry over the many coming months before the decision may be eventually given.

However, the MoEF should remember their clear statement in the 11th January Supreme Court hearing when asked by the bench “Are you completely opposed to mining or under certain conditions you will allow mining?” Solicitor General Mohan Parasaran – acting for the MoEF told the court: “We are completely against the mining operations.”

Confusion is in Vedanta’s interests

The confusion over the meaning of the Supreme Court’s verdict and the proceedings now taking place is evident in the vastly varying newspaper reports coming in daily. The Orissa Post for example stated on Saturday 1st June that:

The department had issued a direction to the District Collectors of Rayagada and Kalahandi to invite fresh claims within six weeks from the people of 12 villages where the Gram Sabhas would be held. After collecting the claims from the people, the Government will hold Palli Sabhas within three months and then it will hold Gram Sabhas in these villages. However, the date of holding Gram Sabhas is not yet decided.

Palli sabhas are in fact the same as gram sabhas, and these have to be held within three months from Saturday’s announcement. The weak and confusing wording of the verdict has already delayed the process by six weeks while the Odisha Government claimed it was clarifying it’s interpretation, and there is much potential for further delays as either side may file ‘contempt of court’ or other resolution which would send the issue back into the court room.

Meanwhile, with share prices already low, factories and mines shut at Lanjigarh, Tuticorin and Goa, and Niyamgiri looking less and less likely, Vedanta are following their usual method of high debt, high risk buyouts to keep the share prices afloat. They are currently pushing the Central Government to sell them the remaining shares in BALCO and Hindustan Zinc ltd, and delaying tactics on the Niyamgiri case will give them more time to potentially save their skin in case Niyamgiri doesn’t come through.

Dragging out the process is exhausting and resource draining for the Dongria and Kutia Konds and local activists and is often used as a tactic to wear down resistance until people eventually capitulate from sheer exhaustion. However, in Niyamgiri’s case this looks very unlikely. The high turnout and defiant energy of the recent Padayatra shows the great strength of Niyamgiri’s people, who have recently been supporting other movements such as the struggle against the Lower Suktel Dam. Lingaraj Azad’s speech at the Padayatra’s final rally in Muniguda also clearly stated that the fight goes beyond Niyamgiri and beyond Vedanta. They are aware that as long as there is bauxite in their mountain they will always have to remain vigilant and ready to respond to threats.