9th August: Ten of twelve Palli Sabhas have now been held on the Niyamgiri hills and each one has unanimously rejected Vedanta’s proposed mine, and laid claim to the whole mountain range for their cultural and religious rights.

9th August: Ten of twelve Palli Sabhas have now been held on the Niyamgiri hills and each one has unanimously rejected Vedanta’s proposed mine, and laid claim to the whole mountain range for their cultural and religious rights.

The latest meeting to be held was in Lakhpadar on 7th August where 97 voters virulently opposed the project and rejected the claims which the judge claimed were filed for compensation of Forest Rights. Local resident and movement leader Lodo Sikoka told the judge and the panel:

“Our God lives in open space. You keep your God locked with a key. We won’t leave Niyamgiri. If the Government, Political Party Leaders ask for it we will fight and shed blood. Why do the police, armed force destroy our fields and crops in the name of combing Maoists? Why are they entering our territory? Withdraw them immediately.”

A full report of the Lakhpadar palli sabha entitled – ‘Niyamgiri is our doctor we will die for niyamgiri but never allow for mining bauxite for Vedanta‘ can be found at Orissabarta.

On 1st August, as Vedanta’s AGM was faced with loud demonstrations in London, 38 of 46 voters attended the Lamba palli sabha in heavy rains. Once again the voters voiced strong opposition to the mine and repeated the statements of other palli sabhas that the whole mountain is both sacred, and crucial to the survival of, the Dongria Kond, and other villagers.

“We can’t live without our Niyamraja which gives us food, shelter and livelihood,” said one villager.

Earlier, on 30th July, Ijurupa – the smallest village of the twelve – held its Palli Sabha. The four voters from just two families living there were present and voted unanimously again to oppose the project. One of the families cooked food for all the visitors after the meeting. Lavanya Kata, one of the participants stated in the meeting:

“You can imagine rehabilitating [us] somewhere but what about the tiger, bear, animals and birds where will you Government Company keep them? We also worship our mountain like people from this land and outside of our area.”

A full report of the Ijurupa meeting from Down to Earth can be found below.

Ijurupa, where a family of four nailed down a 72 MT mining proposal

Sayantan Bera Jul 31, 2013

It’s the eighth village to reject proposed mining in a row in Niyamgiri hills

The irony was unmistakable. To take the opinion of four forest dwellers belonging to one family on the proposed bauxite mining next door, the entire state machinery was present in full swing in Ijurupa village on July 30. Somewhere in his 80s, Labanya Gouda was taken aback by the overbearing presence of 15 cars, government officials, paramilitary forces, a district judge, scores of journalists and activists at his doorstep. The family huddled inside the tent with a heavy downpour outside.

The irony was unmistakable. To take the opinion of four forest dwellers belonging to one family on the proposed bauxite mining next door, the entire state machinery was present in full swing in Ijurupa village on July 30. Somewhere in his 80s, Labanya Gouda was taken aback by the overbearing presence of 15 cars, government officials, paramilitary forces, a district judge, scores of journalists and activists at his doorstep. The family huddled inside the tent with a heavy downpour outside.

Ijurupa is at the entrance to the Niyamgiri hills in Kalahandi district of Odisha. The bauxite-rich flat top hills—proposed mining site spanning 660 ha—is barely one and a half kilometre from his house. The four members of the Gouda family beat expectations by rejecting the mining proposal unanimously in the Palli Sabha or village council meeting. Activists had earlier alleged that the state government selected the one-family village, leaving more than 100 other villages that will be affected by mining, to rig results in its favour. Yesterday, Ijurupa became the 8th village in a row to reject the proposal to mine the Niyamgiris for 72 million tonnes of bauxite. Four remaining villages from Rayagada district—Lamba, Lakhpadar, Khambesi and Jarappa—will take a call on between August 1 and 19 and are widely expected to reject proposed mining.

Pursuant to a landmark judgement by the Supreme Court in April this year, the Odisha government drew up a list of 12 villages spread across Rayagada and Kalahandi districts, adjacent to the proposed mining site, to decide if bauxite mining to feed Vedanta’s Alumina refinery in Lanjigarh will infringe on religious and cultural rights of the tribal and non-tribal forest dwellers. The Dongria and Kutia Kondh tribals worship Niyamgiri forests as their source of sustenance due its perennial streams and bountiful produce and as the abode of their supreme deity and ancestral kin, Niyamraja.

“Niyamraja has looked after me and my grandchildren for all these years,” said overwhelmed Labanya Gouda at the Palli Sabha. “Where will I go if the hills are mined?” he asked after a long silence.

“Niyamraja has looked after me and my grandchildren for all these years,” said overwhelmed Labanya Gouda at the Palli Sabha. “Where will I go if the hills are mined?” he asked after a long silence.

“I have never seen so much of the government before,” continued Dhana Gouda, Labanya’s son. “You might shift us to a city to make way for the mines but where will our wild leopards and bears go?”

A few days ago when this correspondent had visited Ijurupa, the Goudas informed they sold Rs 40,000 worth of cauliflowers last year, grown on the foothills. Besides, the family have mango trees, plots of shift and burn cultivation to grow a mix of native millets and oil seeds, along with a vegetable garden. Gouda’s extended family with four sons and two daughters survive on the bounty of Niyamgiri. Labanya Gouda’s grandson now studies at a regional Industrial Training Institute, in preparation, if the family is shunted out for mining. With all forest villages registering their opinion against mining, such a possibility looks bleak in the near future.

Ijurupa is famous for another reason. In 2010, Rahul Gandhi, vice president of the Indian National Congress, visited the village to meet the Dongria and Kutia Kondh tribals and famously said: “I will be your foot soldier in Delhi.” With a Congress-run government at the Centre, ever since, the mining project has faced hurdles and the proactive state of Odisha has been on a collision course with Union ministries.

Labanya Gouda showed this correspondent the place where a makeshift toilet was prepared for Rahul Gandhi’s hour-long stay at Ijurupa. A tube well was also installed which stopped working later. Not that the Goudas care much. “There is plenty of water in the (perennial) streams,’ he said.

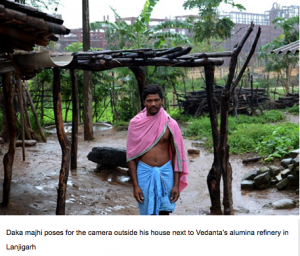

On the way back, this correspondent visited Daka Majhi in Bandguda village. He lives adjacent to Vedanta’s Lanjigarh refinery. He was forced to part with four hectares for the refinery. The promised job never came by. The Rs 1 lakh per acre (0.4 ha) compensation he received was spent on health emergencies and marriages in the family. “Vedanta asked me to join the Industrial Training Institute before I could get the promised job,” tells Majhi, in his 30s. The mockery was not lost on Majhi for he never attended a school. Majhi still treks to the Niyamgiri hills to collect wild roots and tubers to even out uncertainties of being a casual labourer.

On the way back, this correspondent visited Daka Majhi in Bandguda village. He lives adjacent to Vedanta’s Lanjigarh refinery. He was forced to part with four hectares for the refinery. The promised job never came by. The Rs 1 lakh per acre (0.4 ha) compensation he received was spent on health emergencies and marriages in the family. “Vedanta asked me to join the Industrial Training Institute before I could get the promised job,” tells Majhi, in his 30s. The mockery was not lost on Majhi for he never attended a school. Majhi still treks to the Niyamgiri hills to collect wild roots and tubers to even out uncertainties of being a casual labourer.